Planning Your Spring Garden: Why Your USDA Hardiness Zone Matters

I know spring might not be at the top of your mind right now, Garden Bestie—but if you’re dreaming of a thriving 2026 garden, planning today will give you a major head start. Before you sketch out a single bed or buy a seed packet, there’s one thing every gardener needs to understand: your USDA Hardiness Zone and your frost dates.

This guide breaks down the basics so you can walk into spring confident and prepared, no matter where you’re growing. As a Florida girl gardening in Zone 9b, I’m sharing what I know best along with universal tips you can use wherever you live. For advice tailored to your exact region, check in with your local extension office, seasoned gardeners, and growers in your zone.

What Is the USDA Hardiness Zone Map?

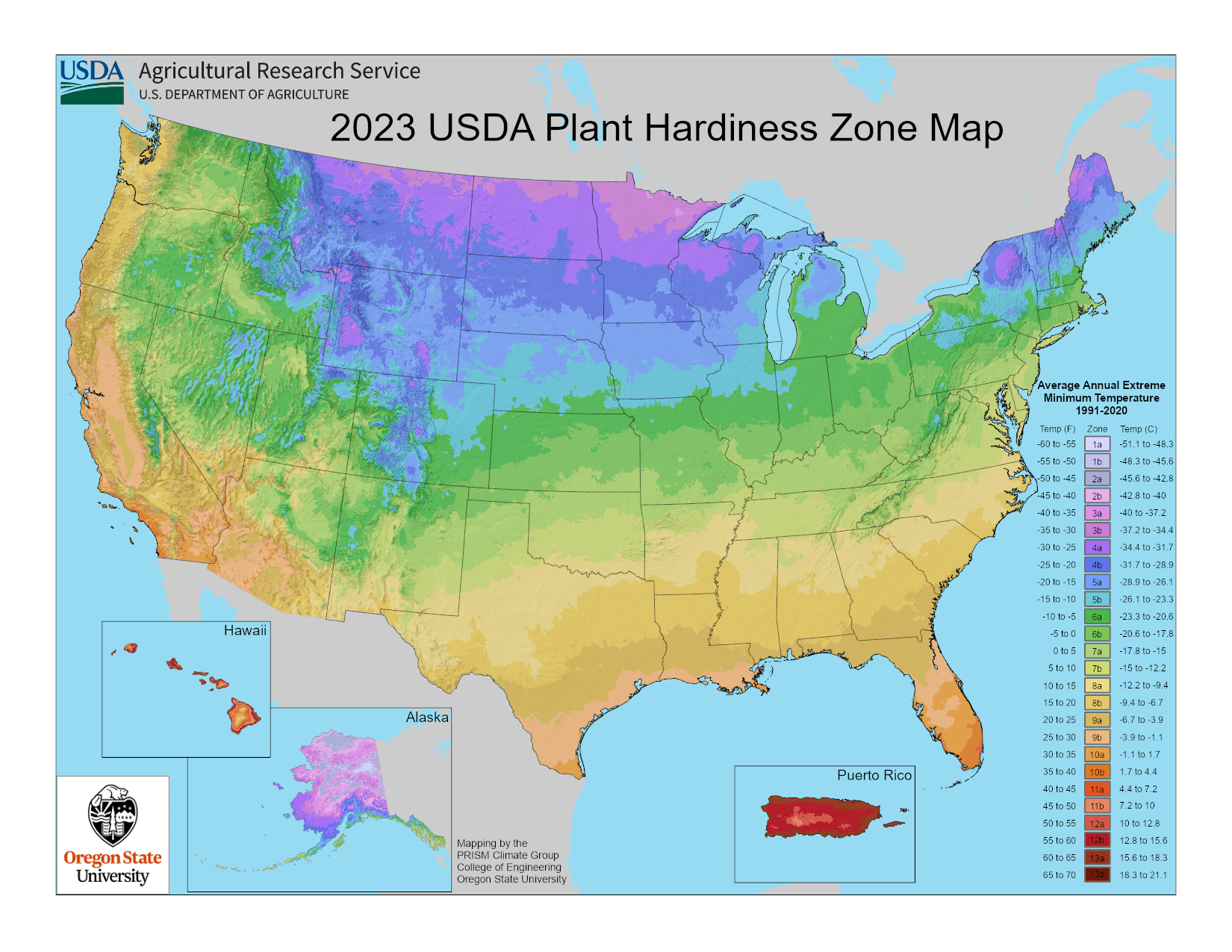

The USDA Hardiness Zone Map was first developed in 1960 to help gardeners figure out which plants can survive their region’s winter temperatures. The map is divided into 13 zones, based on the average annual minimum winter temperature. A lower zone = colder winters. A higher zone = milder winters.

The map has been updated several times over the decades, with the most recent update in 2023 to reflect ongoing climate changes. The official USDA website now lets you plug in your ZIP code to find your exact zone—no guessing needed.

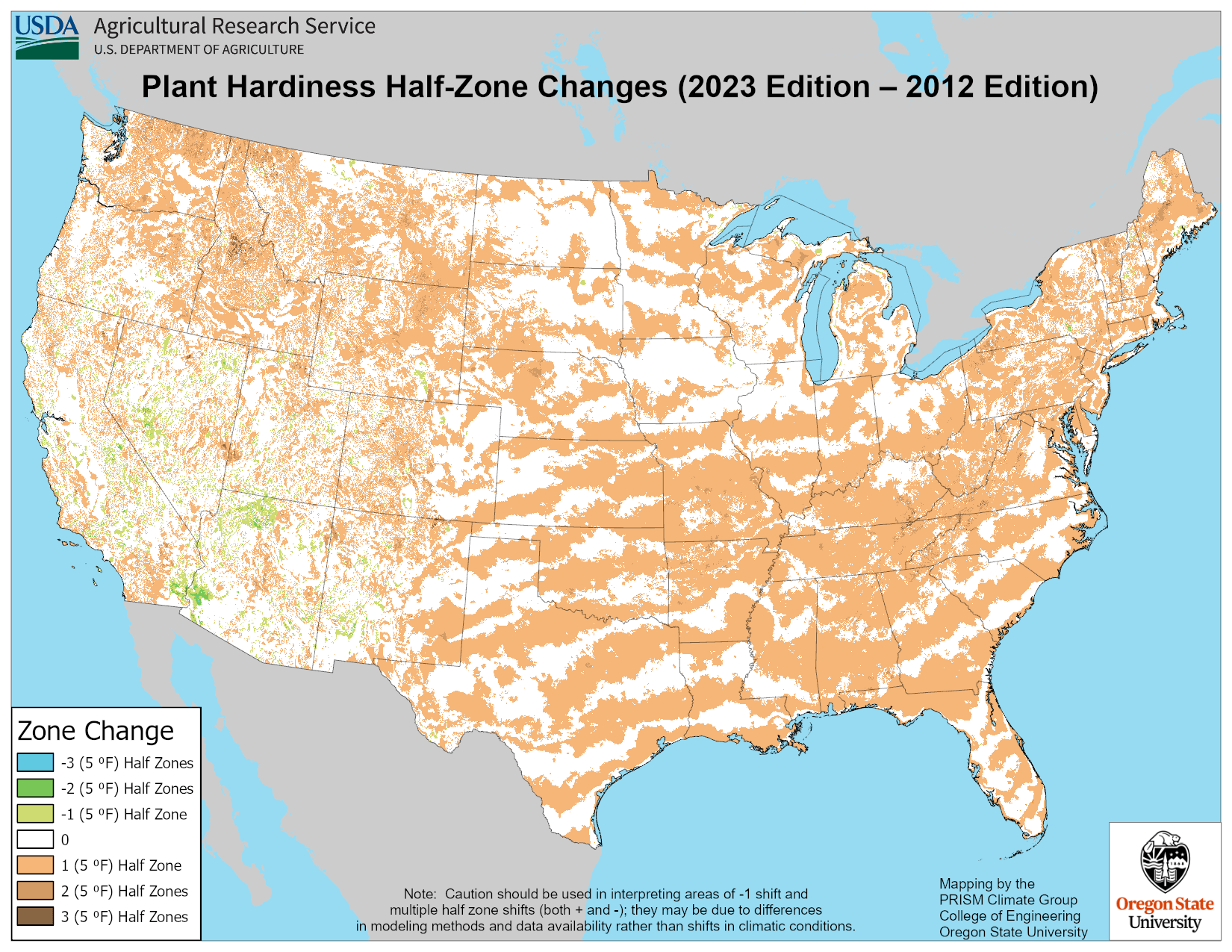

What Changed in 2023?

The 2023 USDA zone update used data from more than 13,000 weather stations across the country, nearly double the number used in 2012. Because of warming trends, about half the U.S. shifted into slightly warmer zones. This matters because:

Plants that once struggled may now thrive.

Some cool-weather crops may need more shade or seasonal adjustments.

Gardeners have more precise data to plan their planting schedules.

If you haven’t checked your zone in a while, now’s a great time to confirm it.

Frost Dates: Your Garden’s True Start and End Points

Your last frost date (spring) and first frost date (fall) are the real anchors of your gardening year. They determine:

When to start seeds

When to transplant

When your crops will mature

How many successions you can grow

I personally use The Old Farmer’s Almanac each year because their frost-date estimates are some of the most reliable. However, frost dates are based on historical averages, so treat them as guides, not guarantees. I always recommend staying flexible and waiting at least two weeks after your predicted last frost before planting frost-sensitive crops like tomatoes and peppers. It’s not uncommon for a surprise cold snap to roll in even after your estimated frost date.

Frost Date Overview by Region

Northern Zones (1–4)

Short growing season, cool summers, and long winters.

Last frost: Late May–early June

First frost: Late August–September

Because the frost-free window is so small, gardeners in these zones often rely on tools and techniques that help them maximize every warm day. Cold frames, low tunnels, and greenhouses are incredibly valuable for starting seeds earlier and protecting plants later into the fall. Quick-maturing and cold-tolerant varieties, like early tomatoes, shell peas, kale, radishes, and lettuces, are staples because they produce well before frost returns.Many gardeners also start seeds indoors very early (sometimes as early as February) under grow lights to ensure plants are ready to go into the garden the moment weather allows. Season extension methods such as row covers, mulches, and even heat-retaining stones help stretch the growing season by a few precious weeks.

Middle Zones (5–8)

A longer, more flexible growing season.

Last frost: Late March–early May

First frost: Late October–mid-November

This range of zones offers some of the most versatile gardening conditions. Gardeners can grow an extensive variety of spring, summer, and fall crops, including long-season vegetables like tomatoes, peppers, squash, and melons, while still enjoying cool-weather favorites like broccoli, cabbage, carrots, and leafy greens.Because these zones sit in a climatic “sweet spot,” many gardeners take advantage of succession planting to keep their beds productive all season long. For example, they might plant early spring peas or lettuce, follow with summer beans or cucumbers, and then finish with fall crops like kale or garlic.

Season extension tools such as row covers and mulch help buffer against the occasional late spring or early fall frost, making it easier to push planting windows and increase annual yields. Gardeners in these zones often find they can fit two or even three full crop cycles into a single season with proper planning.

Southern Zones (9–11)

Mild winters, rare frost, and long seasons (hello, Zone 9b).

Last frost: Late February

First frost: Early December

Multiple successions are absolutely possible in these zones, but heat management becomes your biggest challenge. In my garden, I rely heavily on shade cloth to protect tender crops from the intense Florida sun. Gardeners in these warmer zones should also consider taking advantage of the mild weather by growing certain crops during nontraditional seasons—for example, planting tomatoes in the fall when pest pressure is lower and temperatures are more manageable.

Microclimates: The Secret Sauce in Every Garden

Your USDA zone is important, but your microclimate is where the magic really happens. Two people can both be gardening in the same zone but have vastly different outcomes based on their individual microclimates.

A microclimate is a pocket of space where the temperature, wind, moisture, or light is slightly different from the surrounding area. This can be:

A tall tree, fence, or building structure

A shaded nook under a tree

A breezy open yard

A raised bed that warms faster

An industrial plant

Even your entire neighborhood based on structures, lakes, or paved areas

It is important that you take the time to observe your yard and figure out the unique elements that create your microclimate.

How Microclimates Influence Gardening

Microclimates can be powerful allies in your garden, helping you:

Grow plants typically suited for warmer zones

Protect cool-weather crops from intense heat

Extend your growing seasons (both spring and fall)

Reduce frost risk in sheltered pockets

But microclimates can also work against you if you’re not aware of them.

For example, my yard sits on a slope surrounded by tall trees and a tall fence. I once planted a fruit tree in a spot that received great sunlight in the summer but almost no sun at all in the winter. Even though I’m in Zone 9b—where that tree should have thrived, the lack of winter light slowed its growth dramatically. Meanwhile, another gardener in my same zone, just a few streets away, might have had excellent success simply because their microclimate offered more consistent light.

This is why understanding your garden’s unique conditions matters just as much as knowing your USDA zone. Microclimates can boost your success, or hold you back, depending on how you work with them.

How to Identify Your Microclimates

Observe: Walk your yard in the morning, midday, afternoon, and evening. Notice:

Where snow or frost melts first

Where puddles form

Which areas stay shaded longer

How sunlight shifts from summer to fall

I learned the hard way that a “full sun” summer spot might only get partial sun in winter. Tracking light year-round helps you place beds and fruit trees more strategically.

Experiment: Try crops that "shouldn’t" work for your zone in protected spots. Last year, I grew fall tomatoes—not common—but the cooler weather and lower pest pressure gave me one of my best harvests.

Tomatoes grown in the fall in USDA Hardiness Zone 9b

Use structures: Fences, buildings, boulders, and walls absorb heat during the day and release it at night.

Add water features: Ponds and fountains naturally regulate temperature and humidity.

Plan your vegetation: Evergreen windbreaks, smart tree placement, and intentional shrub layout can dramatically improve your garden’s performance.

Try raised beds and containers: They warm up quicker, drain better, and can be moved or adjusted to create ideal mini-environments. My grow bags stay in rotation because they let me “chase the sun” across seasons.

Putting It All Together: Plan Before You Plant

Understanding your zone, frost dates, and microclimates is the foundation of a successful spring garden. Once you have that clarity, you’ll know exactly:

What you can grow

When to plant

Where to position your beds

How to protect your crops

How to increase your yields

For example, if you garden in a zone where the last frost date is April 1st and you want to grow tomatoes from seed, you’d start them indoors 6–8 weeks before that date—so around early to mid-February. Then, you’d transplant them outdoors around April 15th, once the soil has warmed and the risk of frost has mostly passed. Even then, it’s smart to keep an eye on the forecast in case a surprise cold snap pops up.

Your most abundant garden begins long before you sow the first seed.

Let’s plan wisely so you can grow beautifully.

Enter Code “Grow Food” for 25% off today on my merch!